Semiotics and Design Research

“DesignWrite” was created by Thomas Anstadt to explore design and business-related topics.

Designing With Meaning

Graphic design is not only about aesthetics, but it is also about meaning. As a graphic designer, it is essential to understand how your visual choices convey messages to an audience and influence their perceptions and responses for successful design outcomes.

Expressive Design

Creative flexibility enables a deeper exploration of ideas and emotions, allowing designers to visualize complex narratives and connect with an audience.

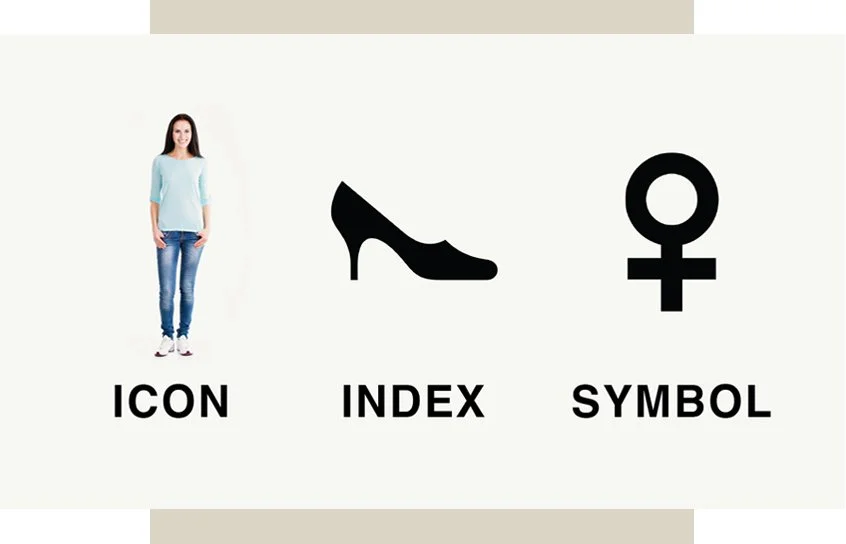

When it comes to graphic design, the study of semiotics can impact the effectiveness of design. Understanding semiotics is crucial for communicating a message clearly and effectively through visuals and type. Designers can create a stronger connection between the design and the audience by utilizing the right visuals, such as icons, indices, and symbols that lead to increased engagement and a more successful outcome for the user.

Semiotics: The Beginning

The workings of language and signs are fascinating. Ferdinand de Saussure, a Swiss linguist, views language as a system of signs. In his lectures on general linguistics, Saussure emphasizes that a sign consists of a signifier (an object) and a signified (meaning). This idea aligns with the semiotic theories of Charles S. Pierce, which delve into how we use language and signs to make sense of our worldly surroundings.

Language and signs create a framework for effective communication that helps us understand the complex world and enhance our interactions.

Image: (L) Ferdinand de Saussure and (R) Charles S. Pierce

Saussure was ultimately concerned with the structure (langue) rather than the use of language (parole). This analytical thinking about the connection between language and meaning became known as structuralism. The basic unit of this structure, the sign, only has meaning because of its difference from others in the same system—the langue.

Meaning emerges from differences, with each sign defined by what it is not, emphasizing the system's role in understanding language.

Image: Sample of sign signifier and signified.

For example, the word bicycle functions in the English language to create the concept or signified as a mode of transportation—a bicycle is a machine with two wheels powered by its rider and used for traveling from A to B. The relationship between the signifier and the signified is arbitrary. There is no logical or natural connection between the spoken or graphic representation and the concept of a bicycle (known as a duality). The link is established solely by its use by English speakers in the same way that different-sounding words describe the same object in various languages, for instance, bicyclette (French) and bicicletta (Italian).

Understanding semiotics research is essential to comprehending how signs function, construct meaning, and impact the perception of a design.By delving into semiotic research, designers can gain valuable insights into how symbols and representations shape our understanding of the world around us. Whether creating advertising campaigns or crafting a work of art, understanding the principles of semiotics can help designers communicate a message more powerfully and effectively.

Semiotics and Creating Successful Outcomes

Semiotics, also known as the study of signs, was coined by Charles S. Pierce, an American philosopher, lexicographer, and polymath. Semiotic researchers study how language and visuals determine how humans comprehend communication. He identified three principal types of semiotic signs: iconic, indexical, and symbolic.

This classification illustrates the mechanisms of meaning in communication and offers a framework for analyzing signs and their function.

Image: The three semiotic sign types.

Iconic signs: These convey the idea of the object they represent by imitating it, such as a photo or drawing of a tree.

Icons serve as powerful visual representations of objects; for example, a photograph of a person is an iconic sign because it resembles the object it depicts. There are also iconic words, where the sound represents the object, as seen with onomatopoeic words like bang or woof.

Indexical signs: These indicate their physical connection with the object they represent, such as smoke indicating fire.

Indices form a direct link between the sign and the object. For instance, smoke is an index of fire, and a tail is an index of a dog. Traffic signs are also index signs. While symbols rely on interpretation, indices depend on the existence of an object; for example, a stop sign with a bullet hole signifies a gunshot. The bullet hole exists regardless of whether anyone makes the connection.

Designers often use semiotics to create concepts with different levels of realism, abstraction, and association.

Symbolic signs: Became associated with their meanings by conventional usages, such as the green, yellow, and red colors used in traffic lights.

Unlike icons or indices, symbols have no logical connection between the sign and its implied meaning; they rely entirely on the reader’s recognition of the link between the symbol and its meaning. The Red Cross, for example, symbolizes aid, while flags represent specific territories or organizations. The letters of the alphabet are also symbolic signs, the meanings of which we have learned.

Semiotic Connotations and Denotations

Icons can have both a literal and subjective meaning, making it crucial to understand the rules and codes of visual language. Imagery and words with double meanings are often combined to create visual concepts in contemporary design. Mastering those rules and codes of communication is essential for designers when creating visual messages.

Connotation and denotation are two terms that describe the different layers of meaning that signs can have.

Denotation: The literal or objective meaning of a sign, such as the definition of a word or the factual description of an image.

Connotation: A subjective or cultural meaning of a sign, such as the emotions, values, or associations that a sign brings forth.

Interpretations of artwork can vary depending upon individual perspectives, experiences, and emotions, rather than objective, universally accepted facts.

Image: “The Witches of Eastwick?”

Depending on the context and the audience, a photograph of a woman holding a straw broom could be interpreted as a mere picture of a woman or a witch.

Depending on the context and the audience, a photograph of a woman holding a straw broom could be either a picture of a woman or a witch.

Designers can evaluate the connotations and denotations of their signs by asking themselves

What do they imply, suggest, or evoke?

How do they relate to the message and audience?

Understanding the difference between the two layers of meaning is crucial when interpreting the purpose of a communication, whether it is visual, written, or spoken. By considering both denotation and connotation, designers understand that the messages they create can have multiple meanings for an audience.

The Design Principles of Semiotic Analysis

Semiotic analysis is a method of interpreting and evaluating signs and their meanings. It involves these four steps:

Description: Describes the signifier and the signified of each sign in the design, such as their color, shape, texture, size, position, and text.

Identification: Labels the sign type, connotation, denotation, design genre, style, and tone.

Interpretation: Explains how the signs interact and create meaning, such as contrast, harmony, balance, hierarchy, and emphasis of the design.

Evaluation: Assesses effectiveness, appropriateness, and persuasiveness of a sign, while considering its goals, audience, and context.

The process of breaking down a text (which can be anything that can be interpreted, like an image, a piece of writing, or even an event) into its component signs and then analyzing how these signs interact to create meaning.

Image: Sample of a Semiotic Analysis board. (sciencedirect.com)

Semiotic feedback refers to the information collected during the testing and evaluation of a design with its audience and stakeholders. It can help designers identify strengths, weaknesses, and improve the design based on semiotic criteria. Some examples of semiotic feedback are:

Communication: How well does the design concept communicate the message?

Clarity: How clear and consistent are the signs in the proposed design concept?

Relevance: How relevant, familiar, and appealing are the signs to the audience?

Originality: How original and distinctive is the proposed design concept?

Trust: How credible and trustworthy is the proposed design concept?

Note: Designers can use semiotic feedback to refine their concept signifiers, signifieds, connotations, denotations, and interactions.

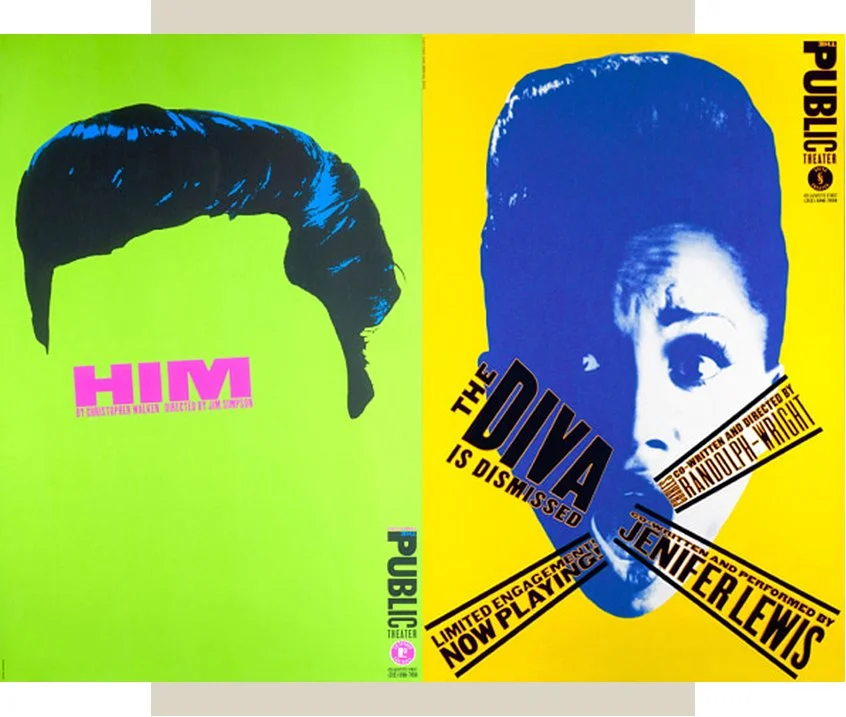

Semiotics as a Creative Tool

Semiotics is not only a tool for design evaluation but also creation. Designers can use semiotics to generate ideas, explore possibilities, and experiment with signs in their design process through the following techniques:

Brainstorm with words, typefaces, images, icons, indices, and symbols.

Use metaphors, analogies, and associations to create new meanings and connections.

Play with ambiguity, irony, paradox, and humor to challenge expectations and provoke reactions.

Mix and match signs from different genres, styles, and cultures to create contrast and diversity.

Designers can add depth and significance to their work by incorporating semiotics into their design process. Semiotics allows for the creation of meaning through symbols, signs, and icons.

Paula Scher is one of the most influential graphic designers in the world. Described as the “master conjurer of the instantly familiar.”

Image: Semiotic design samples by Scher.

Semiotics helps communicate complex ideas and emotions, and adds a touch of creativity to the design outcome. Whether designers are creating logos, websites, or expressive art, semiotics can be a valuable tool to help them create something truly unique and meaningful. It is a valuable tool to help them create something truly unique and meaningful.

In Conclusion

Semiotic theories continue to expand as researchers review, extend, and refine them to increase their precision and the value of the insights they provide when applied to communication. The discovery process is critical to understanding the power and complexity of language and signs, as discussed by Saussure and Pierce, in the design profession.

As we have seen, semiotics plays a significant role in the design process, allowing designers to create specific messages through signs and language. When designers contextually analyze possible words, images, colors, and shapes, they can create powerful and dynamic compositions that communicate a desired message to a specific audience. –end

Please feel free to email Thomas with questions or suggestions about the posted articles. I would appreciate the input.

And please, comment, like and share!